What was the key to changing Americans’ attitudes toward race relations in the ’70s? Some would argue that it was political activism or congressional action or even street protests. I’d say that “All in the Family” was more important than any of those.

What was the key to changing Americans’ attitudes toward race relations in the ’70s? Some would argue that it was political activism or congressional action or even street protests. I’d say that “All in the Family” was more important than any of those.

Do you remember “All in the Family”? If you lived through the ’70s, you probably saw it as a first-run sitcom. If you came along after that, you probably saw some episodes in syndication. After a shaky start — on a network with no real expectations for it — “All in the Family” took off to become the monster sitcom hit of the ’70s, with a long period during which it was No. 1 rated.

The show was about a lovable bigot and his family — his dim-witted wife who sometimes had the biggest heart and best insights, their ultra-liberal daughter and her even more liberal new husband. It might sound like a typical sitcom family, but the subjects were anything but typical. It confronted racial issues and bigotry (among other social issues) in a very up-front way.

The show as a success because it was funny. It was well-written and well-acted. It felt as though its biggest mission was to entertain, not to preach. And that is why it worked better than all the preaching in the world.

There’s no question that political action and rational arguments can have effects at times, especially when it’s strictly about changing laws. But in the long term, it’s more important to change people’s core beliefs than it is to engage their logical conclusions. Thousands of people in the street don’t change minds. Brilliant speeches from passionate advocates rarely really make a difference. Why not?

Do you know the worst possible way to convince a person to change his mind? If you read psychology — especially the psychology of persuasion — you find that the worst thing you can do is tell people they’re wrong. When you do that, you shut down a chance for discussion. The ego can’t deal with it, in most cases. It hurts. And it keeps people from being able to listen to you, even if they suddenly become convinced that you’re correct. (Dale Carnegie quoted an old line that’s applicable here: “A man convinced against his will is of the same opinion still.”)

Let’s look for a minute at how libertarians and anarchists tend to present their persuasive material. If it’s written, it’s very long and very dense (and typically very boring) words that outline the pure logic of a position. If it’s videos, it’s most typically a talking head droning on at the camera with the same sort of very rational material. It’s frequently well-done — perfect for use at the next debate tournament. But the Court of Public Opinion has nothing to do with winning debates. It has to do with subtly changing minds and subtly changing hearts.

“All in the Family” didn’t tell bigots they were wrong. As a matter of fact, the bigot was the protagonist. He was a likable bigot. He was a jerk, too, but he was played as a very human character with strengths and weaknesses. A lot of racial bigots saw themselves in Archie Bunker. And as Archie slowly learned things — through the entertainment of stories — they found themselves learning just a little bit. It didn’t change anything overnight. But if a racist such as Archie could end up getting along with his black neighbor and learn to accept other societal changes, it made it easier for the viewers to do the same.

“All in the Family” didn’t tell bigots they were wrong. As a matter of fact, the bigot was the protagonist. He was a likable bigot. He was a jerk, too, but he was played as a very human character with strengths and weaknesses. A lot of racial bigots saw themselves in Archie Bunker. And as Archie slowly learned things — through the entertainment of stories — they found themselves learning just a little bit. It didn’t change anything overnight. But if a racist such as Archie could end up getting along with his black neighbor and learn to accept other societal changes, it made it easier for the viewers to do the same.

What are the implications of this for those of us who would like to spread individual liberty and teach people not to trust the state? The lesson is that the way to change things is through culture — through arts and entertainment. If we can entertain people, we can get people to listen to our ideas who would never otherwise notice that “weirdos” such as us exist — and they won’t even realize they were listening to our political philosophy.

Those in the liberty movement have spent millions and millions of dollars and countless hours passing out pamphlets and using elections as opportunities to “educate” people. What do we have to show for it? I would argue that it’s not much. There’s still a core group of people who have essentially libertarian beliefs, but we’re not expanding that core very much in percentage terms. We’re still an extremely marginalized minority.

What if we funneled some of that effort toward entertainment? What if we were able to raise $10 million to make five low-budget feature films — entertainment that just happens to contain our ideas at the core? Even before we get to that level, what if we could raise $150,000? For even that paltry sum, a small team could put together four to six high-quality short films — and potentially get huge exposure online and even at film festivals.

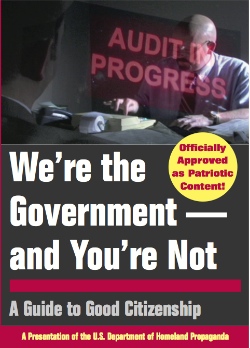

I’m going to use my own short film as an example. I made “We’re the Government — and You’re Not” six years ago on a wing and a prayer, paying the paltry expenses out of my own pocket. I’d been wanting to make a film for something like 15 years, but fears and doubts had stopped me. I finally had a script that I liked and I found the right incentive to make me actually take the big step. (As with most big incentives in life for men, it involved wanting to make an impression on a woman, but that’s a different story.) I made a film with very little budget and learned more than you can imagine. When I was finished, I thought I’d be lucky if a few hundred people ever saw it.

I’m going to use my own short film as an example. I made “We’re the Government — and You’re Not” six years ago on a wing and a prayer, paying the paltry expenses out of my own pocket. I’d been wanting to make a film for something like 15 years, but fears and doubts had stopped me. I finally had a script that I liked and I found the right incentive to make me actually take the big step. (As with most big incentives in life for men, it involved wanting to make an impression on a woman, but that’s a different story.) I made a film with very little budget and learned more than you can imagine. When I was finished, I thought I’d be lucky if a few hundred people ever saw it.

It turns out that short film landed in 20 film festivals, all smaller ones, but still far beyond what I expected. (It was the opening short before a Tim Robbins-directed political feature at a festival in Los Angeles.) It was shown at festivals in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Great Britain in addition to the United States. Surprisingly to me, it even won five awards, including audience awards in a few places. It was quite an unexpected ride.

Then the real exposure started. The last time I checked, it had been viewed more than 300,000 times on YouTube. The best part is that most of the people who watch it aren’t necessarily watching it because they already agree with the ideas. They’re watching it because they hope to be entertained — and the ideas just happen to be there to be discovered along the way.

Most marketing efforts in the liberty movement are very effective with people who are already converted, but have little effect on the rest of the world. We need to think about finding ways to fund projects that can attract mainstream audiences who are looking to be entertained. With a planned effort (even a small one such as the $150,000 plan I mentioned) we could make a small dent in the culture — far more than can be made by printing up more tracts and books and campaign signs.

Of course, I’d be happy if I could raise the money to pursue the films I’d like to make right now, but whoever makes the films — or makes any kind of art that can affect popular culture — is going to have far more effect on the long-term direction of our culture than any political campaign will.

As a filmmaker, I might seem biased, but I think an honest look at the changes brought about for liberal social values in the ’60s and ’70s by television and movies supports this idea. Isn’t it time that we tried something that actually worked?

A haunting question: ‘Where is love now, out here in the dark?’

A haunting question: ‘Where is love now, out here in the dark?’ It’s time to kick the arrogance of ‘American exceptionalism’ to curb

It’s time to kick the arrogance of ‘American exceptionalism’ to curb Warning: Don’t trust in politicians; they’re always going to disappoint

Warning: Don’t trust in politicians; they’re always going to disappoint