In the early 19th century, the United States was an economic backwater with relatively little influence on the rest of the world. There were certainly plenty of natural resources and there were agricultural crops such as cotton and tobacco that were valuable, but the economic centers of the world were in Europe. What happened over the next 150 years that transformed this country and created the highest standard of living in the world?

Things didn’t change because kindly Europeans sent poverty aid to help poor Americans. It changed because Americans took advantage of the opportunity to build businesses and produce valuable goods in ways that were unheard of until the Industrial Revolution. Americans harnessed the market — which was free to a great extent — in order to start up an economic engine that would become the envy of the world.

When we look at places in the world where poverty is crushing and the economy is crippled, why aren’t those people taking the same path that Americans took starting in the 19th century? And for those of us who have serious concerns about global poverty — both the human cost and the violence it brings — what can we do to change things?

Zachary Caceres is a researcher at the Free Cities Institute who’s traveled to poverty-stricken countries to study what factors are holding poor people back. I asked him what he sees and why the help that many westerners are trying to provide isn’t making a long term difference.

“The big issue is symptoms versus diseases,” Caceres said. “Widespread unemployment, informal trading, poverty, extortion by authorities, violence in the streets — these are all symptoms of a dysfunctional social system. It is essentially impossible for the average person in many developing countries to start a business. Should we be surprised then that people have to eke out a tiny living in the streets?”

The problem is that we’re not in the position to change the social and political systems in these countries. So what can we do? For the most part, we end up trying to provide basic services such as relief aid and building wells for safer water and similar things that treat the worst of the symptoms we see. Caceres says those things are good, but they’ll never be enough.

“Charity, emergency aid and other interventions can do plenty of good in moments of sudden tragedy — and they certainly ameliorate some hardship from people’s lives,” he said. “Treating symptoms makes living hard lives easier. But if we are serious about ending poverty, violence and unemployment then we have to cure the disease. This means helping people to make major structural change in their societies.”

“Charity, emergency aid and other interventions can do plenty of good in moments of sudden tragedy — and they certainly ameliorate some hardship from people’s lives,” he said. “Treating symptoms makes living hard lives easier. But if we are serious about ending poverty, violence and unemployment then we have to cure the disease. This means helping people to make major structural change in their societies.”

I told Caceres that my church is active in sending short- and medium-term missions teams to work among poor groups, but that I’ve felt uneasy about the process — feeling that we had to go deeper than the symptoms in order to offer a long-term solution. He agreed.

“People can certainly make a difference in people’s lives by ‘symptom treating,'” Caceres said. “Has your church ever considered starting a business in these areas? Starting a business means bringing expertise from the congregation into the developing world. Profits from the enterprise could go towards wells or feeding people. The beauty of doing it this way is that you are employing, bringing commerce, teaching skills and providing a sustainable fund for ‘food and wells’ that doesn’t rely just on the generosity of your congregants.”

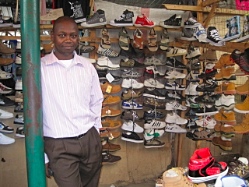

Caceres said that those who want to make a difference need to apply what he called “radical social entrepreneurship” to the problems of the world. He said it’s a way of using entrepreneurial thinking to fix social problems. He gave an example of an idea that came from his time in Kenya studying the informal market there.

“One big and innovative way to help people if you can find a way to buy land is to pool your resources and buy a plot for use as an informal market,” Caceres said. “Land can be very cheap. People in the slums of the world try to do this now but have great difficulty. It can be easier for westerners to get land — often by pairing with a trustworthy local, say someone in your religious congregation from the developing nation. Please note that although this proposal ‘thinks big,’ a small group of people with limited resources can make a big difference in people’s lives with smaller markets.”

You can download a PDF of the proposal for this market here. It’s an excerpt from Caceres’ forthcoming book, “Business, Casual: The Spontaneous Order of the Kenyan Street Trade.”

There was a day when those who went to other countries — such as missionaries — were only interested in saving souls and feeding the people. For many of us, those are still worthy goals, but I think we need to be looking more toward the long-term — how we can join forces to make changes that will restructure societies in ways that can make them prosperous over the next century or more.

Feeding and clothing people is important. Loving them and caring about them is even more important. But there’s no reason why we shouldn’t be equipping the people of the places we want to help with tools that are going to let them — and the generations that come after them — have a greater chance of taking care of themselves.

My church is very active in sending people to help in other countries, but I don’t know of a specific effort to tap the knowledge and skills of business people to find ways that the local people could better help themselves. My church is filled with successful businesspeople. It seems to me that a group of entrepreneurial businesspeople could have a great impact on the future of the people where we send workers. It’s important to feed, teach and build, but what could we do if we helped those people start and run businesses?

My church is very active in sending people to help in other countries, but I don’t know of a specific effort to tap the knowledge and skills of business people to find ways that the local people could better help themselves. My church is filled with successful businesspeople. It seems to me that a group of entrepreneurial businesspeople could have a great impact on the future of the people where we send workers. It’s important to feed, teach and build, but what could we do if we helped those people start and run businesses?

I have big and crazy ideas about what could be done, and it’s something I’d love to be part of under the right circumstances. Can we find places where governments will either co-operate or leave us alone to build businesses with the locals? Can we build new social systems in those countries — formal or informal — that would allow the people to learn entrepreneurial skills (instead of just subsistence skills)? I’ve been thinking about that a lot for much of the past year. It seems like something worth pursuing.

We will never change the poverty of the world as long as we’re just benevolent Americans who show up with some aid money and then leave. We have to partner with local people for the long-term. We have to have people with skills move there to live and work among them. Some missionaries and workers with non-profit agencies are already doing some of this, but I think we can do much more if we’ll apply entrepreneurial thinking — and if we’ll dream really big dreams. Some people will be motivated by faith. Others will be motivated by compassion. Either way, a tremendous amount of hurting can be alleviated.

We can’t fix every problem the world faces, but we can make a huge difference in the lives of people around the world for generations to come if we’ll expand the ways in which we look at aid and ministry.

‘War is the health of the state’ — but the death of the people who serve it

‘War is the health of the state’ — but the death of the people who serve it Best ways for man to love woman flow from how he lives every day

Best ways for man to love woman flow from how he lives every day Could we stop being disappointed by just understanding each other?

Could we stop being disappointed by just understanding each other?