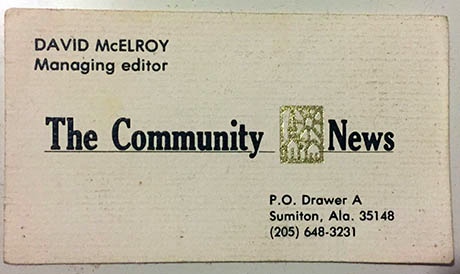

After my junior year of college, I was offered a full-time job that was too good to turn down. The daily newspaper where I’d been working part-time for three years had a weekly newspaper in a smaller town about 15 miles away. The publisher of the smaller paper had taken another job and they needed a new managing editor, too.

Company management decided to take a big chance and offer the job to a brash 20-year-old who hadn’t even finished college.

I didn’t think much of my new boss. He had been the advertising director of the newspaper and had been promoted to publisher. After a couple of meetings with him right before I started the job, I was disdainful of him. Frankly, I thought I was too good for him. I was like an arrogant little child.

My new boss was named Jim. He was fat. He didn’t dress well. He didn’t present himself in an impressive way at all. He constantly smelled like a cigarette butt. He was so fat and out of shape that when I talked with him him on the phone, I would hear him wheezing a little, as though it was hard for him to take in enough air to support all of his weight.

I just saw him as a divorced loser who was alone in the world. How dare someone make him my boss?

As I started going out into the community as managing editor of the paper, I felt such a sense of shame about being associated with such a loser that I made it clear — quietly and subtly at first — how I felt about him. I was afraid of people thinking I was like him. I was embarrassed — more like humiliated — at the thought of anyone thinking he was really my superior.

I didn’t know it at the time, but my feelings about him were triggered by my own fears about myself. I felt such shame about my own fears of inadequacy that I transferred that onto Jim. I made him the focus of my own fears about myself. A person who had been secure in who he was wouldn’t have felt the need to let everyone know what disdain I felt for my boss, especially since he generally let me get away with murder otherwise. He pretty much let me run the news side of the paper as I saw fit. I had little to complain about — and I had plenty that I needed to fix about myself.

After I’d been in the job for about eight months, Jim told me he needed to meet with me at the office of the daily newspaper when we went there to print our paper one week. We went to a conference room and he closed the door.

Jim told me that he had been told that I had been going around town talking badly about him. He knew that I had been criticizing him and he knew specifics. As I had gotten bolder in sharing my disdain for Jim, I had apparently mouthed off to people who didn’t say anything to me, but who reported back to Jim. Several people had all told him the same story, he said.

I lied to him. I denied everything.

This was back in the part of my life when I considered the ability to lie to be a life skill rather than a character flaw. He knew I was lying. We both knew what was going on, but I couldn’t tell the truth.

Jim told me that the publisher of the daily newspaper had given him permission to fire me. I was floored. I felt shame and humiliation and anger. I felt all of the shameful things that had triggered my disdain to start with.

But I was lucky that day. The managing editor of the daily paper wanted me to be his sports editor, because the job was open and he knew my work. So I could either be fired or I could take the sports editor job at the bigger paper.

And that’s how I came to get a promotion and a raise — with a better job — when I should have been fired for gross insubordination.

Jim is dead now. I wouldn’t be telling this story otherwise, because there’s no way I would admit to him at this point in my life just how deeply I had betrayed someone who had been part of taking a chance on giving me a big break. But over the last decade or so — as I’ve come to a deeper and deeper understanding of my childhood and the forces that shaped me — I’ve continued to come back to this story and think about what it says about my relationship to shame.

Although it’s been many years and I’ve grown a lot since then, I still struggle with shame. I feel a deep sense of shame about not being perfect. I feel humiliation because of the voice that’s constantly in my head — barking out my faults and telling me everything that’s wrong with me.

For many years, people told me that I was a perfectionist, but I didn’t believe them. As many things as I allowed to be imperfect in my life, that couldn’t be, because a perfectionist would obviously be driven to live a perfect life. Right? Wrong.

I’ve come to realize that I am indeed a perfectionist, even though I’ve made some progress in changing that. I have believed that I was required to be perfect. In the few areas in which I felt competent to do a good job — mostly my professional life — I delivered as close to perfection as I could get. I was meticulous.

In other parts of my life, I felt like a miserable failure because I wasn’t perfect. I couldn’t control my eating and my weight at times, so I believed that no woman could possibly love me. I couldn’t keep my house in perfect condition, so I eventually felt so overwhelmed that I didn’t try. In one area after another, I realized that I couldn’t be perfect, so I felt shame and humiliation. As a result, I didn’t even try in those areas. I simply listened to a voice in my head condemn me for not being good enough.

In the last few years, I’ve worked hard at dealing with my perfectionism and my deep sense of shame about my lack of perfection. It hasn’t always been easy, but I’m making progress. I’ve discovered that my biggest tools are honesty and vulnerability.

I now have a strong need to be transparent and vulnerable about who I am and what my feelings are, especially with the rare person who I really love, but even with the public to an extent. Obviously, I haven’t always been this way, and it took me a long time to understand why it’s so important to me.

I can be terribly insecure and have a serious fear of criticism. I desperately need to be loved, understood and admired — and even to be placed on a pedestal at times. If I hide those fears and needs, it’s easy for me to present myself in an idealized and grandiose fashion. It would be easy to fall into the narcissistic trap, because that’s what I used to see as normal.

As a defense against what I could so easily allow to happen, I started ripping myself open for everyone to see. I’ve done that more and more, gradually, over the past few years. A narcissist builds a “false self” to present to the world. Before I even understood what narcissism was — when I simply had a vague understanding of what I was fighting in my programming — I started pushing myself to be aggressively open with who and what I am. The more I do that, the tougher it is for a grandiose false self to take root.

For me, being very open about many of my thoughts and feelings — especially as they relate to my own faults and growth — is a form of therapy. By laying myself open and trusting that someone can love what I am — as I am — I’m trying to avoid the pattern I once learned, that of building a false self which has to be dishonestly maintained.

If you’re telling people the details about certain flaws and fears, it’s harder to feel shame about those things. It’s harder to be grandiose. It’s harder to deflect the truth about what’s happened. It’s easier to be real.

I’ve written several times in the past about vulnerability, especially as I discovered the work of Dr. Brené Brown. (Watch her TED talk which originally grabbed me strongly several years ago.) If anything I’m saying about shame and perfectionism resonates with you, watch her TED talk and dive into her books. I also strongly recommend a six-hour series of audio lectures she did called “The Power of Vulnerability.”

I will never be completely over my feelings of shame about being inadequate and imperfect. It still pops up in many random confrontations, especially with anyone I see as an authority figure. (Just last Friday, I had a mild interaction that most people would have brushed off as inconsequential, but it left me shaken, angry and shamed for most of the afternoon.)

A psychologist told me years ago that I’ll never be completely over some of the feelings I have, because they’re buried too deeply. The best I can do is to help those around me to understand my triggers and to continue working to find more emotionally healthy ways of interacting with the world.

When I look back at the ways in which I was disdainful of my old boss Jim, I see a man who was struggling in life to overcome his prior mistakes. I see someone who was nice and decent — someone who tried to be helpful to others, even if he didn’t present the image I wanted him to present. Even if he was not perfect in the ways I wanted him to be.

I’m not like Jim in specific ways, but the irony is that I can see some of myself over the last decade in what he was. That’s sobering and humbling.

I was disdainful of Jim because I was afraid I wasn’t good enough. I’m still afraid I’m not good enough. I’m still afraid that those with better choices won’t choose to love me or do business with me. And I wonder now if Jim had some of those same fears about himself back then.

Call it irony. Call it karma. But I’ve learned a lot about myself by how I treated Jim. If I could apologize to him today, I like to think I would. The next best thing I can do is to keep learning and growing.

I’m starting to believe that I can be OK exactly as who I really am. The best part of that is that it allows me to more easily accept imperfection in others, too, just as long as they’re honest and vulnerable with me, too.

I don’t like the person I was when I was 20. I don’t even like the person I was a decade ago. I hope I can finally become a person who I can completely accept by the time I die. I’ve been working on it for a lifetime. I’m not finished yet.

Major parties compete to see who can tell the biggest lie about jobs

Major parties compete to see who can tell the biggest lie about jobs Hurt people hurt people, and it’s hard to forgive that in ourselves

Hurt people hurt people, and it’s hard to forgive that in ourselves This is why people are confused about what anarchists really are

This is why people are confused about what anarchists really are