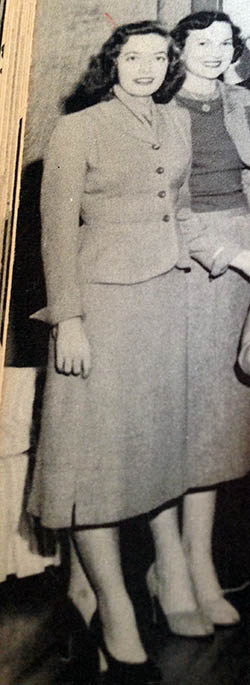

I grew up knowing that my mother was beautiful.

I grew up knowing that my mother was beautiful.

That was what everybody said. I saw old pictures of her from her college yearbook, in which she had been selected as a “campus beauty” by her fellow students. But until recently, I haven’t really comprehended that she was truly beautiful.

To me, she was just Mother. Now that she’s gone, I realize she was objectively beautiful to other people in a way I could never see. I get that now.

This seems to have been typical of my relationship with a mother who I knew, but didn’t know. I’ve spent my life thinking I knew her — what she looked like, what she sounded like, what she did, why she did the things she did — and I’ve constantly had to re-interpret what I thought I knew.

That re-interpretation continues on this Mother’s Day — which happens to be my birthday as well — and I suspect it always will continue, because I have a need to come up with my own answers about her. For too long, I believed the things other people told me to believe about her. I can’t do that anymore.

The happiest memories I have of my childhood come from my very early years — when I felt secure in her love — when I spent my days with her and my two very young sisters while my father was either at work or out of town on business. The memories I have of our days together when I was about 3 and 4 years old — when we lived in Birmingham and then a suburb of Washington, D.C. — make me feel emotional.

I felt happy. Those were the last days in my childhood which I remember feeling happy.

Mother was fun. Everybody liked her and she could make friends anywhere. She had been elected secretary of her college student government. She majored in English and minored in history, if I remember correctly. (My father majored in history and minored in English. It always seemed oddly appropriate that their choices were reversed.)

Mother was fun. Everybody liked her and she could make friends anywhere. She had been elected secretary of her college student government. She majored in English and minored in history, if I remember correctly. (My father majored in history and minored in English. It always seemed oddly appropriate that their choices were reversed.)

She was highly intelligent. She was creative. She was light-hearted. But when she got serious about something, she could communicate with me in a way that touched my heart and made me listen.

She read to us all the time. She didn’t just read children’s stories — although there were plenty of those — but she read us whole books that were advanced for little children. We would read a little bit from a book every day and then stop as something was about to happen. Getting the next episode of the stories in those books was something I constantly looked forward to. (More than once, she read us “The Secret Garden,” and that book was lodged in my heart for good.)

Before I knew it, my sisters and I were accustomed to dealing with stories far more complex than our friends were. This set me on a path that made me a constant reader as I grew up. We made up our own stories. Mother was endlessly inventive with the stories in those early days. One of my sisters was only 2 and the other was a newborn in those early days, so it was mostly Mother and me bouncing story ideas — mostly silliness — between us at that time.

I couldn’t tell you a single story we invented together, but I cherish the memories of her intelligence and gentle humor. Most of all, she took my thoughts and ideas seriously. She took me seriously — and that meant the world to me.

Mother took me to my first movie when I was 3 years old. We went to see Disney’s “The Sword and the Stone” at the Melba Theatre in Birmingham. According to her handwriting in my baby book, “David watched it well and enjoyed it, but he grew sleepy at the very end. We ate popcorn, an orange drink, a Three Musketeers bar and a Hershey.”

Mother took me to my first movie when I was 3 years old. We went to see Disney’s “The Sword and the Stone” at the Melba Theatre in Birmingham. According to her handwriting in my baby book, “David watched it well and enjoyed it, but he grew sleepy at the very end. We ate popcorn, an orange drink, a Three Musketeers bar and a Hershey.”

I felt love and contentment with Mother.

In the next few years, all of that was to change. Mother became increasingly depressed and unhappy. At the time, I blamed her for everything — because my father taught me to do that. I understand now that he was largely to blame.

By the time I was about 5, she had tried to leave my father and take her children with her at least twice. My father wouldn’t let her go. I remember many angry fights with them screaming at one another. She was hurting and miserable. For some reason, they seemed to argue even more when we were in the car as a family.

I can remember going down the road and having my father screaming at her. I didn’t understand why they were angry. I just knew that I wanted the screaming to stop. I wanted our calm and happy days to return.

My father started poisoning my thoughts and feelings about Mother around that time. He would always do it in a way designed to pretend he wasn’t doing what he was doing. It was always manipulative.

“I don’t want to say anything bad about your mother,” he would say smoothly, “but as my mother told me, even a mother dog won’t leave her puppies.”

By that time, she had left to live on her own most of the time, but they were still married. He hadn’t allowed her to take us, but he had allowed her to leave on her own. She told me later that one of them would have ended up dead if she had stayed. She would have killed him or killed herself.

My father needed us on his side, because he was scheming about how he would get custody of the children if they divorced. Everything my mother did which made her look bad, he would document and record names of witnesses — people who had no idea what had caused things that happened.

I lost my mother sometime during those years.

It’s hard to say when. Maybe it was when she was taken away for shock treatments in a mental hospital after she attacked my father when I was 5. I’m not sure. I just know that I never again had the consistent experience of her that had meant so much to me as a small child.

After about the age of 14 or so, I didn’t have any contact with her until I was in college. I was living in Tuscaloosa as a student at the University of Alabama, but one night my long-time girlfriend and I were in Birmingham. On the spur of the moment, I decided to call Mother.

She was re-married at the time, but I found their names in the phone book. I called and she was happy to hear from me. I asked her to meet us somewhere and she immediately left her house to meet in a restaurant.

I introduced her to my girlfriend — who I was planning to marry at the time — and we sat and talked for a couple of hours. It was a strange experience. She was exactly who she had always been — but then she wasn’t. I couldn’t quite put my finger on what was different.

I just knew that my mother felt like a stranger.

She was very happy to talk with me, but that was the last time I would see her for a few years. The next time I saw her, I suddenly drove to Birmingham one day and found the school where she taught third grade. I waited in the faculty parking lot — and then greeted her when she came to her car.

She had divorced again by then — she had bad judgment about choosing men, it seems — and we went to her house in a modest suburb nearby. For the next decade or so — more than that, I guess — I would see her from time to time, sometimes more often and sometimes less.

I was constantly trying to figure out who she was. I was constantly trying to figure out my relationship with her. I didn’t know it at the time, but I wanted to find the mother I had known when I was 3 or 4. I was hoping she was still in there and that I could find her. I needed her, even if I didn’t quite understand that.

I don’t know exactly what she had become by then. I could give you my observations for days, but I never found the vibrant and happy woman who I had known. Life had hurt her badly. She had been damaged by a couple of husbands and years of anti-depressants.

She was still happy-go-lucky. She still played Christmas music whenever it suited her, whether it was close to Christmas or not. She still danced around the house to her music. She was still intelligent and wise at times.

But I never found whatever it was I was looking for.

By the end of my relationship with her, my own life was starting to have problems. She was becoming more and more child-like. She might call me when I was in the middle of working and announce that she was at a doctor’s office and that I had to come get her — right now.

It wasn’t like a command. She wasn’t mean. It was more like the action of an immature child who didn’t know she was imposing or that she should make plans ahead of time. I had to get involved with fixing her bill with a drug store that made deliveries. She had run up a huge bill — mostly frivolous things such as candy and soft drinks, at high prices — for herself and a young girl she frequently kept. She was like a child who couldn’t understand why she couldn’t just get whatever she wanted, even though it left her with a huge bill she couldn’t pay.

I went through a lot with her during those years. I was there with her while she had knee replacements. (Or were they hip replacements? It’s hard to recall now.) I helped her move to a rehab facility for awhile. I spent a lot of time at her house. I ended up keeping her cat, Dusty, when she had to move to a facility where she couldn’t take him.

But in all the things I did with her, I never found the person I was hoping to find. I don’t know whether she was simply too hurt and damaged — or if my memory of what she could be had been too distorted by an idealized version of my early childhood.

I’ll never know for sure.

But I’ve finally figured out something. It probably shouldn’t have surprised me. In fact, it seems obvious now that I think about it.

Every woman I’ve ever fallen in love with has been compared to those early memories of my mother. If a woman couldn’t be the sort of loving and caring and devoted mother that I remembered of my early mother being, I wasn’t interested in her.

In a very real way, I have always been looking for a mother for my future children — someone who could be for them what my early mother had been for me — even more than I was looking for a woman to be my partner.

I’ve wanted — and I still want — a woman who will make children feel just as loved and understood and secure as Mother made me feel in those early years. Is that a bad standard? I don’t think so. The most important decision you’ll ever make for your children is who the other parent will be. (The next most important decision is who you’re going to allow them to grow up with.)

I don’t yet know what to think about my mother. I know she loved me. I know she did what she thought was best for her sanity and survival over the years. I know that every decision she made has to be seen through the lens of the domineering narcissist who was my father.

I’m sure she wasn’t the ideal mother who I believed her to be when I was young, but I know she wasn’t the crazy person who my father convinced me to believe her to be. There’s a lot I’ll never understand about what she became, but now that both of my parents are dead, I’m believing more and more that she was a lot closer to the wonderful mother I had believed in as a child.

Mother was a complicated woman. She made decisions for reasons that weren’t always easy for me to understand. I can’t go back into her past and figure out what happened to her. My gut feeling is that my narcissistic father and primitive electroshock therapy did a lot to change her.

I cherished that loving and wonderful mother who I had in my early years. I still miss her. I still need her, even though I’ll never be able to find that version of her again.

Mother was beautiful.

She was intelligent.

She was creative.

She was sensitive and kind and loving.

She had a huge heart.

She listened to me and cared about everything I had to say.

Mother was so much of what every child needs.

As the years go by, I’m ever more grateful for the experience I had with Mother in those early years — before she was taken from my life, never to return as the woman I had known.

I loved her — and Mother loved me more than anybody else ever has.

Note: The upper two photos were from one of Mother’s college yearbooks at Jacksonville State University. They’re slightly distorted because they were photographed from the book instead of being scanned. The picture below is of Mother in the mirror of her hospital room at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Birmingham in the days after giving birth to me.

We’re neither friends nor enemies, just strangers who share the past

We’re neither friends nor enemies, just strangers who share the past ‘This path leads to somewhere I think I can finally say, I’m home’

‘This path leads to somewhere I think I can finally say, I’m home’ Society needs storytellers to help make sense of a changing world

Society needs storytellers to help make sense of a changing world