On the surface, this is a story about food and obesity. Underneath, though, it’s a much deeper story — about science, economics, prejudice and how humans arrive at their version of truth. It’s complicated and messy, but the lessons are applicable across the board — including in politics.

On the surface, this is a story about food and obesity. Underneath, though, it’s a much deeper story — about science, economics, prejudice and how humans arrive at their version of truth. It’s complicated and messy, but the lessons are applicable across the board — including in politics.

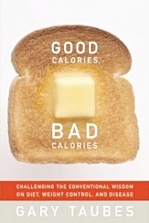

Over the last 50 years, it’s become medical wisdom that eating fat is a very bad thing. It causes obesity. It clogs arteries. It causes all sorts of problems. But what if there’s no proof of that? What if every study ever attempted to prove it had done the opposite or been inconclusive? Science writer Gary Taubes says that’s the case.

Taubes researched the history of the recommendations against fat and the various efforts to prove that approach is the right one. He also looked at the competing theory about obesity, heart disease and other health problems — that they’re caused by sugar. His evidence will leave you wondering why you ever worried so much about fat.

His book is called “Good Calories, Bad Calories: Fats, Carbs, and the Controversial Science of Diet and Health,” but you don’t have to read the book to be fascinated by its insights, both about nutrition and about how science determines what’s true and what’s not. (If you’re honest, it might make you wonder how honest you can really be with yourself.) On this week’s episode of EconTalk, economist Russ Roberts interviews Taubes. Click “play” to listen.

[haiku url=”http://files.libertyfund.org/econtalk/y2011/Taubesfat.mp3″ title=”EconTalk: Taubes on Fat, Sugar and Scientific Discovery” graphical=”true”]

One of my biggest fears is that I’m wrong about some of the things I believe. I don’t mean that I’m afraid of having to admit to error. I simply mean that I’m afraid I’m wrong about things I’m unaware of. Unless I think I’m now perfect — and I don’t — I must be wrong about some things. And how would I know which things I’m wrong about? How much of what I believe is prejudice or bias? How much of it is just a gut feeling backed up by noticing whatever evidence favors my position and ignoring evidence to the contrary?

In the interview — which I hope you just listened to — host Russ Roberts quotes something profound from the late physicist Richard Feynman, who said, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool.” Many of us tend to believe that would be true about other people, but surely not us. The smarter we are — and more accustomed we are to feeling that we’re right — the more we might be susceptible to fooling ourselves.

Based on the evidence I’ve collected over the last 20 years or so, I’d say that doctors (and then politicians and bureaucrats) who bought into the anti-fat narrative — and forced it on the country as official policy — have fooled themselves. The idea started with one man with one observation in the late ’50s. When he started selling the idea — with absolutely no evidence — he was able to get the American Heart Association to buy his narrative. And it spread from there. How much of commonly accepted wisdom is just as poorly supported by facts?

The more I observe people and learn about human psychology, the more I’m certain that people aren’t nearly as logical and factual as they believe they are. (I include myself in that, of course.) I’ve had a theory for years that we arrive at conclusions for emotional reasons and then choose to pay attention to whatever facts support what we believe is true, while completely ignoring the facts that provide evidence against our narrative.

People who are big believers in the power of their own reasoning believe that other people can “come around” to their way of thinking if they’re simply provided with enough facts and reasoning. I don’t believe that anymore. I believe we’re always going to disagree, because we’ll all pull out the facts and reasoning to support whatever we emotionally need to believe. But most of us will be completely unaware of what we’re doing, so we’ll assume that everyone else is being irrational.

People who are big believers in the power of their own reasoning believe that other people can “come around” to their way of thinking if they’re simply provided with enough facts and reasoning. I don’t believe that anymore. I believe we’re always going to disagree, because we’ll all pull out the facts and reasoning to support whatever we emotionally need to believe. But most of us will be completely unaware of what we’re doing, so we’ll assume that everyone else is being irrational.

This points — once again — to the need to structure the world in a way that people can disagree about the rules they live by, whether it’s about what they eat or how their neighborhoods look or what their rights are in regard to what they produce. I don’t want to live in a “one size fits all” world where a coercive state takes from me what it wants — and dictates what my choices are, whether those choices are about what foods I should eat or what I should do with my money or what countries my money is used to invade.

I’m going to read Taubes’ book, partly because I’m interested in the fat vs. sugar war. (I’ve been on the anti-sugar side for a long time. It’s my biggest weakness.) But I’ll also read it because of its insights into human nature and the prejudices we all bring to the search for truth and the fights over the “right” way to structure society.

There has to be a better way of arriving at conclusions about what truth is than what we do now, because our current system doesn’t work very well for any of us.

Feds to trucking co.: You can’t fire the drunk, but you’re liable for him

Feds to trucking co.: You can’t fire the drunk, but you’re liable for him Corruption trial prosecutor wrong: Power is for sale to highest bidder

Corruption trial prosecutor wrong: Power is for sale to highest bidder Relationships he couldn’t mend were the real tragedy of my father’s death

Relationships he couldn’t mend were the real tragedy of my father’s death