A curious thing happened in Europe 97 years ago this week. Men who had been trying to kill each other suddenly stopped shooting. They started singing together, exchanging Christmas greetings and giving one another presents. But when the authorities from their respective governments got involved, they had to give it up. They were forced to go back to killing each other.

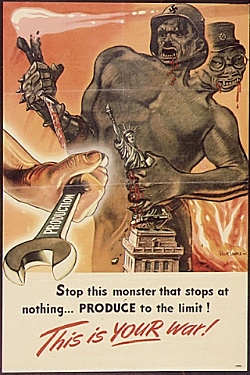

Human societies spend a lot of time and effort to keep a tiny minority of people from hurting and killing each other. Governments have elaborate systems of police and courts to protect most people — who just want to be left alone — from that tiny minority. But when politicians get angry with each other across borders, they expect something quite absurd. They expect people who want to live in peace to suddenly hate other people enough to kill them. The desire for peace is a hard thing for the politicians to get out of stubborn humans.

The narrative we normally hear is just the opposite — that humans are so violent and so war-like that society would be nothing but chaos and killing without benevolent governments agreeing to control things. But the evidence suggests that the story is far more complex than that.

The Christmas truce of 1914 was very unofficial. It wasn’t observed in all places. But in the midst of the slaughter of World War I — seen as the Great War to end all wars at the time — British, German and French soldiers spontaneously made temporary peace with one another. They came out of their trenches and socialized. Obviously, the didn’t hate one another.

In his controversial book, “Men Against Fire,” U.S. Army historian S.L.A. Marshall claimed that 75 percent of U.S. infantry soldiers under fire during World War II never fired their weapons at the enemy with the intent to kill. (His conclusions were controversial and not everyone accepted them, so decide for yourself.) Lt. Col. Dave Grossman, who is a psychologist and professor of military science, looked at Marshall’s evidence and concluded that “there is within most men an intense resistance to killing their fellow man. A resistance so strong that, in many circumstances, soldiers on the battlefield will die before they can overcome it.”

Because of Marshall’s research, military training has changed since then — in order to make it more impersonal and automatic. The military wants soldiers who act more like machines, who kill as they’re ordered to kill. The last thing they want is men and women who can think for themselves — and who can ask themselves why they might possibly want to kill the people their government is telling them to kill.

And here you have a paradox of the state when it comes to killing. When it suits the state’s purpose, it will use all of its powers to keep a small number of people from killing. But remember that most people never have to be restrained from killing. If there were no government and no police, most people would still never kill. In fact, most people are so peaceful that they have to be victims of endless propaganda to get them to follow orders. They have to be subjected to psychological training techniques designed to overcome their peaceful nature. Is it any wonder that so many soldiers have trouble returning to peaceful civilian life? (Even after all the propaganda they’ve been subjected to, only 50 percent of returning U.S. troops say the war in Afghanistan was worth it. Only 44 percent say that the Iraq war was worth it.)

I would encourage you to read more about the Christmas truce of 1914, because it’s interesting history. (Here’s another detailed article about it, too.) Mostly, though, I’d like for you to think about the fact that ordinary British and German and French infantrymen had no reason to kill each other. They were only firing at each other because their governments dictated it. The governments were the ones with the grievances. The politicians had made alliances that compelled people to try to kill each other.

I would encourage you to read more about the Christmas truce of 1914, because it’s interesting history. (Here’s another detailed article about it, too.) Mostly, though, I’d like for you to think about the fact that ordinary British and German and French infantrymen had no reason to kill each other. They were only firing at each other because their governments dictated it. The governments were the ones with the grievances. The politicians had made alliances that compelled people to try to kill each other.

Those people weren’t angry at each other. They had more in common than anything else. Most of them just wanted to go home and live in peace. The truth is that war happens when a tiny percentage of people gain power and use psychological propaganda to persuade the majority that people in other lands are their enemies. Our real enemies are those people with the power over us and the people who have power over the people in distant lands. The ordinary people aren’t our enemies. The state is our enemy.

If coercive governments don’t exist in the future, there will certainly be a small number of people who will still die, because some tiny percentage of people are going to try to kill a tiny percentage of other people. But the massive killings of millions of people — or even tens of thousands of people — won’t be possible without coercive states. It seems like a very worthwhile tradeoff to make.

Addendum: I had meant to use this H.L. Mencken quote in this story, but it slipped my mind. It’s too good not to add here, though: “Wars are seldom caused by spontaneous hatreds between people, for peoples in general are too ignorant of one another to have grievances and too indifferent to what goes on beyond their borders to plan conquests. They must be urged to the slaughter by politicians who know how to alarm them.”

Ban on saggy pants: Why do we require laws against looking foolish?

Ban on saggy pants: Why do we require laws against looking foolish? When we feel we’ve lost control, our behavior stops making sense

When we feel we’ve lost control, our behavior stops making sense Against all rational choice of will, an old hunger in my heart returns

Against all rational choice of will, an old hunger in my heart returns