IRONDALE, Ala. — I’m writing this on my iPhone in a small monastery chapel before I can forget what I’ve been thinking about — because no matter how many times I learn the truth I experience, I let it slip away and I forget.

IRONDALE, Ala. — I’m writing this on my iPhone in a small monastery chapel before I can forget what I’ve been thinking about — because no matter how many times I learn the truth I experience, I let it slip away and I forget.

I keep forgetting what the truth is. I keep focusing on the wrong things. I keep forgetting who I am. I keep forgetting what’s important in life. I keep forgetting who and what God is. I forget because God has to be experienced in the silence, not drowned out by the din of a world that’s not especially interested in experiencing Him.

I feel as though I know less about God than I did when I entered this world as an otherwise ignorant and innocent child. I suspect children are born knowing more about the truth than we realize, but they forget it as they’re taught how to think and act like the rest of us. Sometimes, though, I can catch a glimpse of a child’s knowledge through my experiences with God.

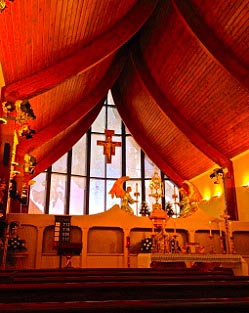

I’m in the chapel at Our Lady of Angels Monastery, which is located less than 10 miles from my house. Although I’m not Catholic, I find their chapel to be a wonderful place for contemplation and prayer. The picture shows the view from my back-row pew right now.

I don’t believe that certain places are actually “sacred space,” but some music, some art and some environments make me feel as though there’s space inside of me that’s ready to connect with God. This is one of them.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the differences between the world of the rational and material and the world of spiritual experience. I started out in life pretty close to being a complete rationalist. (My earliest serious career interests were engineering and law, if that tells you anything.) But the longer I live, the more I trust my subjective experiences — and the less trust I place in what used to seem so solid and logical.

The experience of God — just from being quiet and still and listening — is being devalued in many churches today. I think it’s a symptom of an age when almost everyone is accustomed to being entertained every moment, in addition to it reflecting the attitudes of the broader world that something has to be measurable and explainable or it doesn’t exist.

But the most real experiences I have today are the ones that aren’t measurable and science certainly wouldn’t explain them other than to dismiss them as the products of chemical activity in my brain that made me feel something that’s imaginary. In my heart, though, I know that the presence I feel in silences such as today are real — more real than the material world that seems so easy to measure and to over-value

I don’t know how to live effectively with one foot in each world. I want to live in the spiritual world of God’s presence, but my body has to exist in the material world for now. I have brief experiences of feeling connection with what I’ve come to call God. It’s not a bearded old man in a white robe. It’s something so much bigger and deeper than that.

When the 19th century American evangelist Charles Finney wrote about his first experience with God, he struggled to explain what it felt like. He was a lawyer who wasn’t sure he even believed in God, but his experience one day left him completely changed. In his account of what happened, he wrote, “I could feel the impression, like a wave of electricity, going through and through me. Indeed it seemed to come in waves and waves of liquid love; for I could not express it in any other way.”

Every time I have an experience that feels as though I’ve made contact with God, I feel as though Finney’s phrase makes sense to me. It always feels like “waves and waves of liquid love.”

I’m essentially a rationalist. I like explanations and I keep searching for them. I’ve had a tendency at times — well, most of the time — to over-think things. That’s why I can’t write poetry, for instance. If I tried to write poetry or song lyrics, I would end up writing complete sentences that felt like prose. I think when I need to feel at times.

But when I have these experiences, I have to feel. I can’t help it. There’s no rational explanation. There’s only acceptance of something that feels more real than anything else in the world. As Finney described said, it simply feels like love.

My faith was once all about being rational and having the right interpretations of scripture. I still have opinions about a lot of things when it comes to scripture, but I’m finding it more honest to say, “I don’t know,” about more and more things. I’m finding that it’s much more meaningful to focus on the experience I feel and less on what different people argue about theology.

The truth about God is felt, not thought. Our thoughts do our best to summarize what we’ve felt, but those words are a dim imitation of the feeling — the experience — itself. Is this why traditional religious art emphasized beauty over functional meaning? How much have we given up in the modern church by making the discussion so much about function — the things we can touch and measure in our fancy church program — rather than the truth and beauty that we feel inside?

I used to think that I had something to say about God that was of use to other people, expressed in my fine arguments about theology. (Back when I was in college, I was an avid reader of Christian apologetics and I later moved on to Christian philosophers such as Francis Schaeffer.)

Now, it seems that all I can do is honestly report my own experiences and suggest that people go deeply inside to listen to what God is always saying, even when we’re too busy talking. When you’re in the middle of experiencing truth, the mundane parts of life — who won a football game or where you’re having dinner or whether your clothes are new and stylish — don’t matter very much.

Many devout modern Christians can explain their church’s doctrines, but they don’t have much — or any — experience with God. They’re simply repeating what they’ve been told is true — and that’s not enough.

The great psychologist Carl Jung experienced something of a world beyond the material world, too. He wasn’t always sure what it was, but he understood its importance. He said, “We should not pretend to understand the world only by the intellect; we apprehend it just as much by feeling. Therefore, the judgment of the intellect is, at best, only the half of truth, and must, if it be honest, also come to an understanding of its inadequacy.”

The great psychologist Carl Jung experienced something of a world beyond the material world, too. He wasn’t always sure what it was, but he understood its importance. He said, “We should not pretend to understand the world only by the intellect; we apprehend it just as much by feeling. Therefore, the judgment of the intellect is, at best, only the half of truth, and must, if it be honest, also come to an understanding of its inadequacy.”

I’m glad we live in a rational age when science understands so much more than what humans understood a hundred years ago, much less centuries ago. I’m very appreciative of what science and reason have given us. I wouldn’t want to lose them. As someone whose mind tends to work in a very logical way, I love reason.

But I can’t deny the truth of my experience. God isn’t a bearded man on a throne. He also isn’t a myth, although much of what’s said about Him is. He’s something much bigger than that. And when I touch Him, it feels like love.

When I get too busy and loud and overwhelmed, I forget all that. I want to remind myself, because I need that experience of love — over and over, again and again.

I’m struggling with video project, and I’d like to share the reasons

I’m struggling with video project, and I’d like to share the reasons Why do we put off changes that might give meaning to our lives?

Why do we put off changes that might give meaning to our lives?