For years, doctors have been looking for one gene to blame for problems such as depression and schizophrenia. A couple of new studies have dashed those hopes, because it seems that dozens or even hundreds of genes are involved. The doctors involved in the study were disappointed. I was relieved.

For years, doctors have been looking for one gene to blame for problems such as depression and schizophrenia. A couple of new studies have dashed those hopes, because it seems that dozens or even hundreds of genes are involved. The doctors involved in the study were disappointed. I was relieved.

If you could take a pill — or get a shot or have an operation — to “fix” some way in which you’re different from other people, would you do it? With some things, the answer is clearly, “Yes.” If you were blind or deaf or had damaged vocal chords, most people would gladly make the change.

With other things, the answer is pretty clearly, “No.” If you’re left-handed, you don’t want to be made right-handed. If your eyes are blue or green, you don’t want to change your eyes to brown just because it’s the most common thing in the world. For other things, the answer is more gray? Do you remove a mole that you’ve been worried about all your life? Do you straighten your nose? For most of us, we conclude that we’d rather be what we were born with in most areas, simply because it’s who we are.

If the questions and answers are that complicated for your physical body, how much more complicated are they for the mind? We can sometimes see our bodies as physical shells we ride around in on Earth, but our thoughts and feelings are what make us entirely different from the other people around us, at least as far as our own internal thoughts are concerned. (I’m ignoring the issue of a soul, because this is about psychology and ethics, not about theology.)

If the doctors in one of the studies in the news Monday had come up with one gene to blame for depression or schizophrenia, would you want whatever “cure” they came up with? As long as my life were fairly functional, I know I wouldn’t want it. Whatever goes on inside my brain — and my heart and something on the inside — is what makes me “me,” and I don’t want someone else monkeying around what what I am.

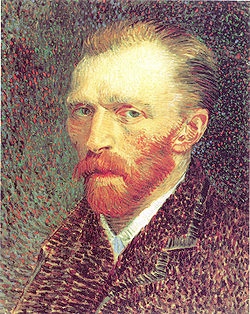

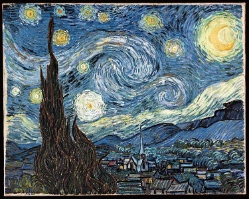

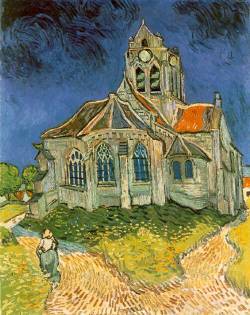

There’s always been a fairly obvious strong correlation between madness and creative genius. In many cases, the most creative artists were also the maddest. (Scientists think they might now understand at least part of the reason for the connection, but I’m not really going to get into that.) The art above is a self-portrait of Vincent van Gogh, who is thought to have suffered from bi-polar disorder or some other issue. I’m going to use a couple of his other works throughout this article. And this is often the case for artists, even though there’s obviously not always that direct a connection. Not all people with mental illnesses are especially creative as far as we can tell, and not every creative genius is “crazy.”

But what if both creativity and mental issues such as depression exist on a continuum? Few people would choose to be truly insane, even if amazing creative genius of some kind came with it. But what if all of our creative types — and I like to think of myself as among them — have just a bit of one of those mental “defects” caused by those dozens or hundreds of genes?

But what if both creativity and mental issues such as depression exist on a continuum? Few people would choose to be truly insane, even if amazing creative genius of some kind came with it. But what if all of our creative types — and I like to think of myself as among them — have just a bit of one of those mental “defects” caused by those dozens or hundreds of genes?

What if our ability to create and to come up with startlingly original ideas comes directly in proportion to our propensity to be bothered by depression or mood swings or worse? Is that something to be “fixed”? Or is it something that makes certain people who they are?

My mother suffered from bi-polar disorder — which we called manic depression back then — so I’ve seen first-hand how it can affect people. I also know that my sisters and I have all inherited various bits and pieces of her tendency to be a bit odd. OK. A lot odd sometimes. (I wrote about my family and some of the ways that being “crazy” had affected me a couple of months ago.)

Here’s the thing. My parents should never have married. She had issues that he was never going to understand. (My family was broken starting when I was about 5, but the back-and-forth madness between them continued for years.) They loved each other, but each had no real understanding of the other. He was about as “normal” — in the genetic sense — as it’s possible to get. She was eccentric and weird and disorganized and a hundred other things he hated. He tried to force her to be like him. It almost killed her. Living the “normal” lie that he forced her to live sent her into a deep depression from which she never recovered. It destroyed their family and hurt their children more than I can tell you.

But the problem wasn’t her craziness. From the vantage point of years later, I see that she could have lived a happy and joyful life if she hadn’t been living with a man who didn’t understand her and who slowly tried harder and harder to change her. (The first few years of their marriage were actually quite happy, they say, until they had children, at which point everything changed.)

So my mother was bi-polar and seemed to suffer from some other issues (possibly a mild case of borderline personality disorder), but she was basically a happy, creative and joyful person away from him. She passed along that creativity and weirdness to her children, who are happy when they’re creating and being weird. I pay a price for it at times in a tendency toward mild depression. I’ve never had the kind that’s been debilitating, but I can’t deny that there’s a piece of it there. I feel things too deeply — both good things and bad things — not to have times of going into a hole.

But here’s why I mention this. I like who I am. I don’t want to be like everyone else. I want to feel things more deeply than others. I want to have crazy ideas and see connections that others don’t make. This is who I am. I don’t need — or want — a “cure” to make me more like everybody else.

But here’s why I mention this. I like who I am. I don’t want to be like everyone else. I want to feel things more deeply than others. I want to have crazy ideas and see connections that others don’t make. This is who I am. I don’t need — or want — a “cure” to make me more like everybody else.

I’m certainly glad that I was born, but I’m sorry for my mother’s sake that she didn’t marry someone who could understand her and live an enjoyable life of mutual craziness. There are millions of other people such as my mother — people who are a little warped and who don’t quite fit. They can be perfectly happy as they are with the right people.

There are many people such as me, those of us who don’t quite fit into the normal world and who can be polarizing and weird and even creative at times. I don’t think most of us want a “cure” for who we are. We are willing to accept the downsides to this along with the upsides — and be content with having to find the rare people who are capable of understanding us.

I understand there is a group of people who are not functional in the world, who have mental problems that go beyond the kind of “functional crazy” that I’m talking about here. For them, finding those genes that make people crazy (and making a change) might be a good thing, on balance. For me, though, taking away the bit of “crazy” that I have would be as bad as a lobotomy. It would take away who and what I am.

It would be nice to fit more into the rest of the world. It would be nice to be understood by more people. It would be nice not to deal with a bit of depression from time to time. But it would be a nightmare to have taken away from me what I am. It would be a terrible tradeoff, because … well … I mostly like being a bit crazy. And I like other “crazy” people. I “get” them — and they “get” me. Few others do. I don’t want a “cure” to change that.

Local politics isn’t a Frank Capra movie; it’s every man for himself

Local politics isn’t a Frank Capra movie; it’s every man for himself My heart longs for a future that’s more real to me than the dim past

My heart longs for a future that’s more real to me than the dim past I just found out an ex got married – and I’m shocked to feel jealous

I just found out an ex got married – and I’m shocked to feel jealous